“I would rather sit on a pumpkin, and have it all to myself, than be crowded on a velvet cushion.” – Henry David Thoreau

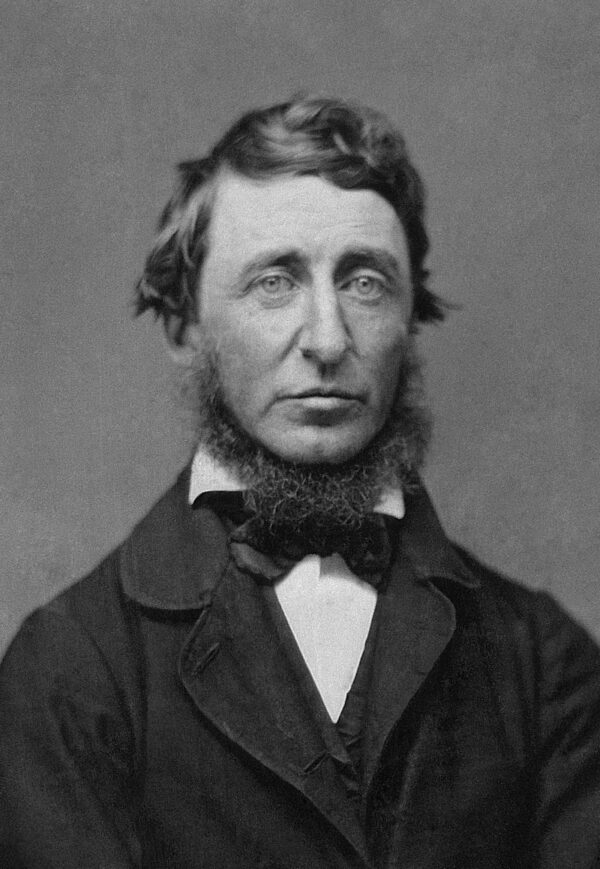

“Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817 – May 6, 1862) was an American essayist, poet and philosopher. A leading transcendentalist, he is best known for his book Walden, a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings, and his essay “Civil Disobedience” (originally published as “Resistance to Civil Government”), an argument for disobedience to an unjust state.” (Wikipedia)

Henry David Thoreau would have been a natural at what we now call “social-distancing.” He could have taught classes on the subject. When he went into the woods he was in his happiest state. He frolicked, almost like a child, and you could describe him as a child at heart, someone who never really grew up in the minds of many around him, in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and the pretensions of Concord and New England’s post-Puritan puritanism – crowded, on a velvet cushion.

Though Thoreau would fit right into the pigeonhole of social distancing in today’s world’s “New Normal,” he would have resisted being shoehorned by an algorithm into the simple binary destination of this or that, left or right, Democrat or Republican, Liberal or Conservative, Blue or Red, BlahBlah or BlahBlahBlah.

He was fiercely anti-slavery (and a strong defender of the Bible-and-sword wielding John Brown) and in that regard is often philosophically aligned with his contemporary, Abraham Lincoln – the first Republican president, although Thoreau died before Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation and didn’t really follow politics at the party level. He was also a headstrong tax-resister and detested what he viewed as an overreaching federal government.

But he hated war – or at least the Mexican-American War, which took place from 1846-1848, when Thoreau was 29-31 years old – and he wouldn’t have fought, being a vocal conscientious objector.

He was also what we would today call an “environmentalist” because he loved nature and hated to see it being raped for the profit of corporations gearing up for the Gilded Age. He tilled and toiled in his bean garden, and let his hair grow long – only bathing in Walden Pond when driven by necessity – so he’d be considered an original flower-child and OG Bohemian; all of which would peg him as a Don’t Tread On Me Gadsden flag-waving Libertarian, card-carrying, first-generation Republican, draft-dodging, acorn-eating Peacenik Hippie Freak who would have gladly kept his six feet of social distancing but would have gone to jail rather than wear a mask – a free-thinking Ivy Leaguer who’d be happier watching a beaver do its work than work the Transcendental sherry parties of the Greater Boston Area.

How many people do you know who would fit that description?

Thoreau was born the son of a pencil maker, to modest means. He was a studious child and went on to attend Harvard, but refused to pay the fee for a diploma which was printed on sheepskin, saying, “Let every sheep keep its own skin.” He was simply following suit with this attitude, as his grandfather had led Harvard’s 1766 “Butter Rebellion”, our nation’s first student protest. The acorn doesn’t fall far from the tree.

My introduction to Henry David Thoreau came in my junior year English class way back in the 70s (the 1970s), when my teacher, who was not afraid to challenge some “norms” on her own, had us read a play called The Night Thoreau Spent in Jail, based on his experience of being put in jail for not paying poll taxes because he didn’t want to support the Mexican-American war and it’s dubious intentions and deceptive incitement by the champion of Manifest Destiny, President James K. Polk, who was hellbent on taking as much land as he could to extend the United States to the Pacific Ocean by whatever means available. He certainly did just that.

There was one line in the book that stuck in my mind. It still does. It came unstuck one day during that summer, while I was working at our family-owned cheese factory in a small farm town in Wisconsin, when my father told me I’d be picking up a Sunday shift for one of my cousins who had decided he’d had enough of working in our family owned cheese factory, and went to work at a different cheese factory owned by a different family. It was only a 4-5 hour shift, since we didn’t make cheese on Sundays but still had to take in the milk from the bulk trucks and can trucks and wax and wrap the wheels of daisy cheddar that we made during the summer “flush” season, when cows grazed in pastures and gave copious amounts their best (fattiest) milk; but it meant I had to be there at 8 am and work with my uncle, whose nickname of Badass pretty much indicates why my cousin went to work at a different cheese factory with a different family in the first place.

I had just gotten my driver’s license and was discovering carnal knowledge as dispensed from the bowling alley in the neighboring town where I went to high school, as the small town where I grew up no longer had enough students to sustain even an elementary school, closing it not long after I had attended along with a half-dozen classmates. It’s an American Legion Post now – and it’s very sustainable.

I remember not being too pleased at being told I’d now have to work 20 days in a row before getting one day off, but that didn’t sway my German Protestant pops who said, “Oh, one more shift isn’t going to kill you. We made cheese seven days a week when I was your age during the summer, before we put in the storage tanks. Sometimes you just gotta work.” He always liked to say that. It even gave him a little smile as he said it. There was never a reason why. It was always, “you just gotta work.” But this time, I had him. Or so I thought…

I looked up at him and asked – earnestly, “Why work like a dog all your life so you can pant for a moment before you die?” He looked at me as though I was speaking some foreign blaspheme or anti-cheese balderdash. “Where the hell did you learn that?” he asked, and when I told him that I’d learned it in school from a play called The Night Thoreau Spent in Jail he said, “Ah, fiddlesticks. I never heard of it,” and he made some attempted humorous comment about jail maybe being a good place for him (Thoreau) if he didn’t want to work. Crazy German Protestant attempted work humor…

So, I picked up the extra shift, and it didn’t kill me. “That which doesn’t kill us makes us stronger,” I said to myself. Some philosopher named Nietzsche had originally said that, I guess, but he wasn’t related to the middle linebacker who played for the Packers under coach Vince Lombardi in the 60s. He was a Kraut, but I doubt if he ever worked in a family cheese factory. But… back to Henry David Thoreau, who wasn’t too crazy about working at his family business making pencils. I don’t blame him. At least you can eat cheese. And fresh curds right out of the vat, paired with an ice-cold Sun Drop citrus soda? Oh, don’t get me going…

I didn’t think of Henry David Thoreau too much for a long time after that, until I was in my 50s and had to have a hip replaced because I’d broken my leg pretty badly in 8th grade playing football and partially ruptured a growth center near my ankle, so after nearly 40 years of toddling around on one leg which was a wee bit shorter than the other, I’d worn all the cartilage out, and walking anywhere was no longer any fun.

I bought his book, Walden, to read while I was recuperating from the surgery at home, because I’d tried to read it a few times earlier but never really got into it. I like the basic storyline of the book – about living on your own in nature and all that – but those Ivy League smart dudes from the old days can be about as interesting to read as making pencils must have been to make. I finally finished it, several years later. I never have that problem with Mark Twain. Just sayin.

Thoreau did, however, say some things in such a way to make them remembered long after he’d passed, and that isn’t necessarily easy. He’s possibly quoted most often for saying, “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” He spent an awful lot of time alone in the wild and very little time with women, so perhaps he was speaking from a limited perspective. I’ll resist the urge to brand him as sexist and rush out to burn his books and statues. He probably wouldn’t have cared anyway.

Regarding his time at Walden Pond and elsewhere in the wilderness of New England, while contemplating Transcendentalism and becoming expert at handling a canoe, he said:

“I went into the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what I had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

“I find it wholesome to be alone the greater part of the time…I love to be alone. I never found the companion that was so companionable as solitude.”

“If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music he hears, however measured or far away.”

And, finally and simply:

“All good things are wild and free.”

But unlike all good things, Thoreau was not always wild and free – not for one night in particular. He may have spent only a night in jail for not paying his taxes (before being bailed out and having his taxes paid, presumably by an aunt who didn’t want the family name to bear embarrassment), but it piqued his interest in challenging the policies of a government he felt was breaching its moral restraints. His essay Civil Disobedience was published in 1849 following the Mexican-American War and in the midst of the conflagrating controversy of allowing slavery for new states being gathered under the false pretense of Manifest Destiny as championed by President Polk.

One night in the slammer gave him a lifetime of contempt for government running amok with hubris and greed. He called upon people’s consciences to limit government growth, which would make him a Reagan Republican. He spoke of the need for the consideration of revolution, which could cast him as a Founding Father Style Patriot. And he also spoke of abolishing government altogether, which brought the label of anarchist. But given the grotesque disparity of all that ideological bumper sticker mumbo jumbo, it seems more likely that Thoreau was an independent thinker not afraid to go against the cultural soup du jour and speak his conscience peacefully. He was a rabble-rouser of ideas, not people. This was long before the incendiary influences of digital “news” and “social” media.

Here are some of his thoughts from that part of his life. He began the essay with this:

“I heartily accept the motto, “That government is best which governs least”; and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and systematically. Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which also I believe – “That government is best which governs not at all”; and when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which they will have. Government is at best but an expedient; but most governments are usually, and all governments are sometimes, inexpedient.”

“I don’t ask for no government, all at once. I ask for better government, all at once.”

“The only obligation which I have a right to assume is to do at any time what I think right. It is truly enough said that a corporation has no conscience; but a corporation of conscientious men is a corporation with a conscience.”

“All men recognize the right of revolution; that is, the right to refuse allegiance to, and to resist, the government, when its tyranny or its inefficiency are great and unendurable.”

“There will never be a really free and enlightened State until the State comes to recognize the individual as a higher and independent power, from which all its own power and authority are derived, and treats him accordingly.”

And then there’s this:

“If we were left solely to the wordy wit of legislators in Congress for our guidance, uncorrected by seasonable experience and the effectual complaints of the people, America would not retain her rank among the nations.”

In these unsettling and transformative moments of future history, Henry David Thoreau would be a quiet wolf howling among the clamorous bleating of sheep, possibly spending more than a night in jail for not following the rules. “Under a government which imprisons any unjustly, the true place for a just man is also a prison.” Sitting on his pumpkin, crotchety and alone, far away from the velvet cushion, he can be heard to unruly utter, “Any fool can make a rule, and any fool will mind it.”

But if he really was alive today, I wonder if Thoreau wouldn’t just go seeking another Walden Pond, leaving the lives of quiet desperation to the mass of humanity, and tend to his garden of beans. And, let’s be honest, would you blame him?

Leave A Comment