“Put the stuff closer together so it’s easier to get to the stuff”

April 30, 2021, On Common Ground By Kurt Buss

This is how Minneapolis planner Paul Mogush describes the 15-minute city concept, which is getting refreshed attention, though it’s hardly a novel method of designing the places where we live. It used to be the status quo in many small towns and rural communities before urban flight and improved highways lead to the advent of suburbia, big box stores and malls; so, we don’t need to start from scratch.

“The 15-minute city is just the latest restatement of what more and more planners, leaders, and everyday people have been realizing, which is that traditional small-town development was elegant, efficient, and beneficial, and that the modern auto-oriented landscape that we’ve moved into has serious drawbacks,” says Tracy Hadden Loh, a fellow with the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Center for Transformative Placemaking at the Brookings Institution.

I know this, having grown up in a small farm town [pop. 250] in central Wisconsin in the 1960s. It once was vibrant, boasting two grocery stores, a community bank, feed mill, cheese factory, farm implement, hardware store, tavern and a ballroom big enough to hold weddings and rock shows. All that is gone now. Rusted-out cars cover the scars where these buildings once stood. It’s a shame. But, there is hope. In many instances, the chickens are coming home to roost. There’s even a phone app that enables anyone to type in an address and see how that neighborhood meets the criteria for a 15-minute city, available at https://app.developer.here.com/15-min-city-map/(link is external), by HERE Technologies.

In a recent Wall Street Journal story, [March 12, 2021] “Small Town Natives Are Moving Back Home,” it was pointed out that, due in part to the COVID-19 pandemic, 52 percent of adults age 18 to 29 lived with their parents in 2020, the largest share since the Great Depression according to Pew Research Center, and that U.S. Census Bureau data has indicated many large metro areas have seen declining growth, and in some cases population losses since 2020.

Telecommuting has lessened the need to drive to a brick-and-mortar office building, reducing stress on overburdened commuter conduits and greenhouse gas emissions, giving people greater choice in where they call home. Quality of life issues make fresh air and fewer urban grievances — from road rage to violent crime — appealing to families seeking a healthy, safer place to raise their children. As the farmer, poet and essayist Wendell Berry said, “No matter how much one may love the world as a whole, one can live fully in it only by living responsibly in some small part of it.”

Leaving a small town, rural area or the suburbs to see other parts of the world will always be an enticement for many, as it was for me. Drawing residents back has been difficult as America flipped from being roughly 80 percent rural and 20 percent urban at the beginning of the 20th century to 80 percent urban and 20 percent rural by the end; but the pendulum is always in motion. Urban decentralization and getting away from car-centric city design is putting more focus on walkable communities as well as meeting the desires of today’s homeowners. A recent NAR community preference study found that 85 percent surveyed said that “sidewalks are a positive factor when purchasing a home, and 79 percent place importance on being within easy walking distance of places.”

Helen D. Johnson, president of the Michigan Municipal League Foundation, has seen how important the notions of proximity and participation are to creating vibrant, inclusive, economically healthy and culturally wealthy communities, and what the parameters are for making this a reality.

“In order for the reality of a 15-minute community to be made real for residents, our local government leaders need to be intentional about understanding what their needs and wants are. Key questions should be asked, such as ‘How can communities co-locate opportunities for healthy living and health care, for education and entertainment, and for food and arts, and other essential amenities?’ And, ‘How might we support local businesses and organizations to provide these amenities sustainably and in a way that provides stable jobs for locals?’ We are supporters of the concept of community wealth building and the effort to share prosperity for all in ways that enhance the human experience. Communities of all shapes and sizes can aspire to achieve community wealth building by creating trust, being collaborative, and by listening to their residents. In the end, it comes down to reaching common ground and realizing we all want the same thing — prosperity.”

But there are obstacles to drawing and retaining residents in small communities and suburbs. Loh identified the primary hurdles. “We have built almost nothing except auto-oriented sprawl for several generations now, and so much of the real estate industry is streamlined to deliver this product, especially in terms of financing. We have to re-learn how to build something else.

“Also, zoning regulatory regimes actually prohibit the kind of walkable, traditional neighborhoods that embody the 15-minute city in most places in the United States. And, we have a lot of obsolete legacy buildings and infrastructure that are literally physically in the way of creating 15-minute neighborhoods, and we have to figure out how to rehabilitate and retrofit that stuff — and how to pay for that work.”

Walkable, complete neighborhoods are not only the desire for new homeowners, but equally important to us baby boomers looking to enjoy what used to be described as the Golden Years. AARP has been active in the concept through its Livable Communities initiative and coined the phrase “20-minute village.” (We boomers walk a little slower and are easily distracted, thus the additional five minutes.)

AARP’s Livable Communities Director Danielle Arigoni, an urban planner by education with more than 20 years of professional experience, including leadership positions at the EPA and HUD, explains: “I think at its root it’s really about increasing choice, and being more mindful of how we design communities so that you can live well without needing to get behind the wheel of a car, which comports very well with what we’re trying to do with our Livable Communities initiative. We’re really about working with communities and supporting local leaders to expand choice in housing and transportation and design places that put the needs for older adults first in the belief that when you do that you actually get to solutions that really benefit people of all ages.

“What we see rural communities doing is taking on placemaking opportunities, where they’re thinking differently about carving out some parking spaces and turning those into little after-dining or parklet situations. We’re seeing more communities recognize that what they need in order to bring people back downtown is maybe more benches or better lighting or wayfinding. And all of these small incremental investments can be done under the age-friendly banner, but the same assets are obviously of value to everyone.”

Strong Towns is a major player in advocating for change in the way urban design can support economic strength and resiliency in less populated locales and suburbs. Its Senior Editor Daniel Herriges discussed how the 15-minute city concept can benefit small towns and rural communities.

“What a small town has working in its favor is that it was designed around people walking. It has storefronts and maybe a park or town square with a gazebo. Neighborhoods are close by. It’s a place that is inherently adaptable to a lifestyle where you walk out your door and you’ve really got the village right there. And I think a small town also often has a sense of identity and community — that a suburb might not necessarily have — where the community is the locus of people’s lives.”

Strong Towns reported on the inexpensive development of an unused downtown space in “Low-Cost Pop-Up Shops Create Big Value in Muskegon, Michigan” [pop. 38,000] where funds derived from the chamber of commerce, a community foundation and other organizations paid for the construction of 12 wooden buildings ranging from 90-150 square feet at a cost of just $5,000 to $6,000 per “chalet.” Small businesses and startups were able to co-locate in an area that brought shoppers back to an untenanted commercial lot and allowed them an affordable entry to operate, in some cases being a stepping stone to moving into a larger storefront. The city has since taken over funding of future pop-up chalets.

“The broader notion of just being willing to lower the bar for what’s the smallest best next step you can take I think is really, really powerful,” Herriges says. “And that’s what they did there, they said we’ve got this land the city’s sitting on and that it owns in our downtown, and there isn’t developer interest in it right now to build a whole big building on it, but we don’t have to let it sit idle in the meantime when there’s something we can do such as a little pop-up use that would begin to draw people into that space. This isn’t something for just the built-up cores of major cities. It applies in rural areas very much, too.”

The National Main Street Center is another active player in small town preservation and revitalization, working to join various municipal and civic organizations to collaborate on projects bringing new life to less-populated communities. Lindsey Wallace, director of Strategic Projects and Design Services, told “On Common Ground” how the 15-minute city concept aligns with its efforts.

“Building partnerships and intentional community engagement are key, particularly as these concepts often necessitate thoughtful physical and infrastructural changes. This is true in communities of all sizes, but particularly in small towns and rural communities, where people wear many hats and may be in the same positions for long tenures.

“We often encourage local leaders to get to know their local planning department, public works, and parks and recreation staff as well as their state departments of transportation so that when an opportunity comes to adopt new policy or try out a complete streets project, you have already built trust and camaraderie. Similarly, consistent, intentional public engagement better connects local leaders with small business owners, residents, and anchor institutions like community colleges and libraries, so local leaders can ascertain and address concerns over changes necessary to achieve 15-minute city concepts — such as conversion of parking.”

While small towns and rural communities are more inclined to be able to offer greater variety in a tighter space through inherent mixed-use zoning in downtown areas, suburbs are a different matter.

“Suburbs are the hardest area to address because of the strict zoning limitations around residential uses only,” Arigoni says. “Subdivisions are really challenging, but I don’t think we can write them off, obviously, because so many people live there. I think the most incremental thing we can do towards that is allow for more diversity of housing in those areas and start with diversifying the housing stock, because that will allow different kinds of people to live there and will allow people to remain there once they no longer have children to raise, for example, but they don’t want to leave their four-bedroom house because they love their neighbors and their community, the social activities and their church is nearby, or whatever.

“What are the options we’re making available to those people in a suburban community? Once more varied housing stock gets incorporated organically into those neighborhoods, then allowing for flexibility in uses so that you can have a live/work situation or offices or small commercial spaces integrated into residential neighborhoods. I think it will take incremental baby steps. I don’t think we’ll get to a point where we’ll see a corner store in a lollypop type neighborhood, but we can gently begin to integrate uses in a way that can improve the quality of life for people.”

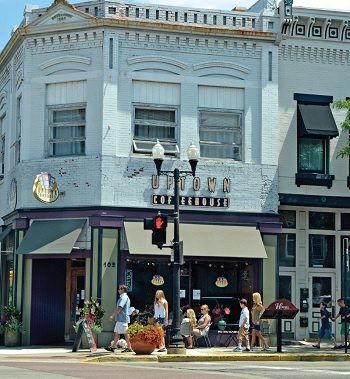

Sensible baby steps in increasing the allowed types of housing stock will diversify the demographic of people able to live in suburbs, with ADUs such as granny pods and in-law cottages allowing the elder birds to stay in the neighborhood once the younger ones have flown the nest. But how do these inhabitants enjoy “the essence of what constitutes the urban experience,” as described by Carlos Moreno of the Sorbonne University in Paris, a champion of the 15-minute concept? What desired destinations can be most easily integrated into the residential fabric of suburbia without affecting the feel of the neighborhood for all its residents? Coffee shops, small bistros and bodegas, perhaps an art gallery/studio or other such “third places” for locals to congregate, connect and participate in their community might be a good start.

“I would say in a suburban context, the planner target is an accessory commercial unit, with the idea of running a home-based business and having some sort of a little makeshift storefront out of your home and legalizing things like that and encouraging that to pop up,” says Herriges. “It’s a landscape that was designed for total separation of uses where all you’ve got is houses. It wasn’t built for walkable access to the things you want of daily life, so you would have to begin to unwind that and graft it on. It’s going be a little ad hoc, it’s going be an improvisational process — and it involves a certain tolerance for chaos. It’s not going to look like a quaint older neighborhood in Chicago or Brooklyn. It’s going to be a little messier, because of where we’re starting from.”

Intentional, incremental collaboration of local governments with civic organizations seems to be a theme among proponents of walkable, bikeable complete neighborhoods, without reinventing the wheel.

“Work with what you already have — small towns, rural areas, and older streetcar suburbs all have the right bones to be 15-minute neighborhoods,” says Loh. “There is no need to start over from scratch.”