Ben gets his first black eye when he’s 12 years old. It’s a good one. One for the books.

It happens at the Caroline Ballroom in 1972, in the small Wisconsin farm-town where Ben grew up, as the wounded veterans are returning from the Vietnam War (which wasn’t considered a “legal” war because it wasn’t “authorized” by Congress, so it was called a “Police Action.” It didn’t involve any police officers, though. We sent soldiers, Marines, fighter/bomber pilots and the Navy. Over 58,000 Americans died in the jungle on the other side of the world, killing commies for mommy. Try telling their families that it wasn’t war. Good luck with that.)

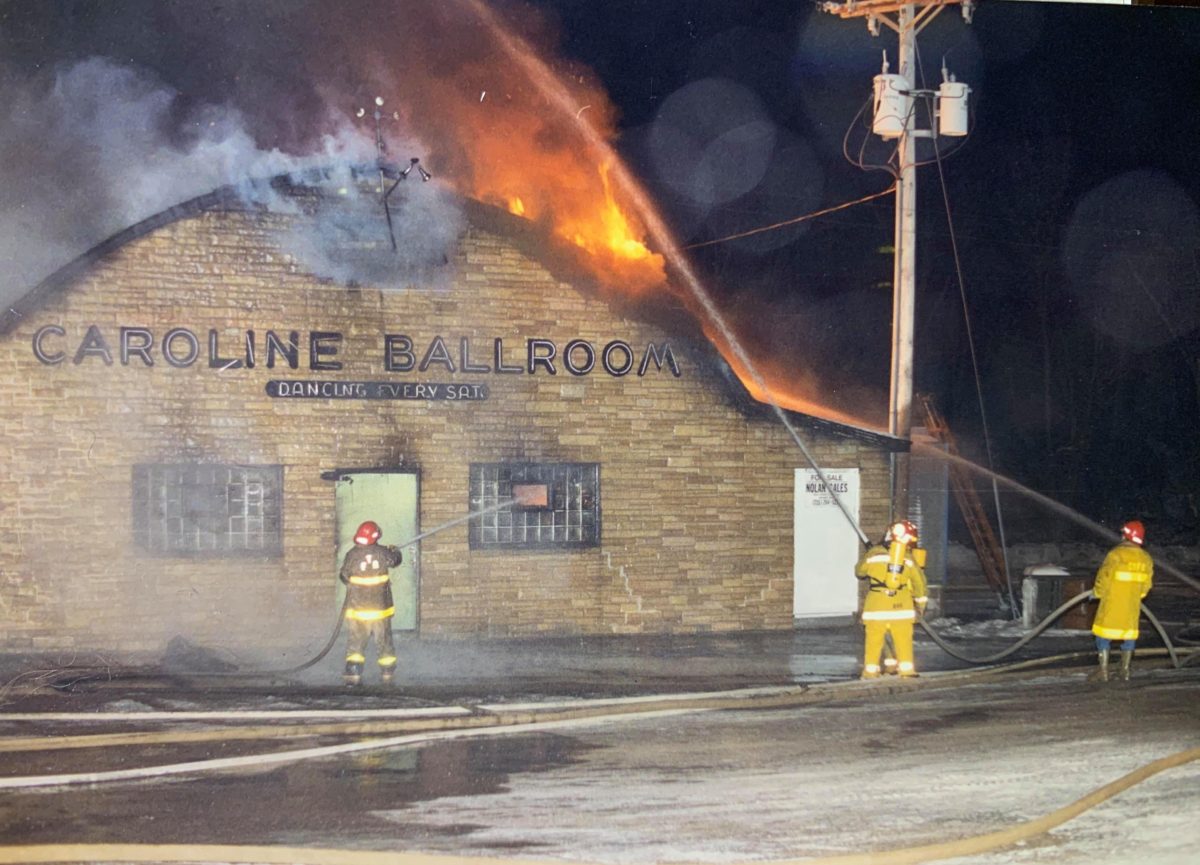

But Ben isn’t a warrior, as he’s soon to find out. He thinks he is at that moment, after being steeled by a few sneaked beers at the wedding reception of a local farm-girl to a local farm-boy. The Ballroom is a great place for wedding receptions, in that German descendant cheesemaking town, and later for freaky-haired, crazy-named rock and roll bands as the 70s takes its post-psychedelic grip. Ben is tall for a 12-year-old, but skinny. Inexperienced in the actions of men, but curious what a fight is like. The floor of the wood-arch domed, voluminous ballroom has been sprinkled with sawdust, so the dancers can shuffle and glide as they turn and twirl to the polka bands with the difficult-to-pronounce Polish names. Ben sees his mark and gives it a shot.

Tommy Rassmossen, (name slightly changed to protect the innocent) known as Rass-Ass, is a few years older but several inches shorter than Ben, and Ben thinks he can take him. When Ben sees him standing in front of the vintage theatre chairs with cast-iron bases and hardwood folding seats and armrests that line the dance floor, he charges Tommy and tackles him, putting his backbone into the protruding end of an armrest. Ben thinks that will be all it takes. He’s wrong. Tommy gets up and looks at Ben in disbelief.

“Ow! Goddamit! Why the hell did you do that? That hurt, you asshole!” Ben doesn’t answer, just raises his fists. “I don’t want to fight you!” Tommy says. “You’re just a kid!” But the adolescent beer-buzz makes Ben feel like a man, so he advances on Tommy, his little fists raised half-way up his torso with his elbows hanging below. He repeats his words, but Ben presses on. By this time, all the other youngbloods are watching, yelling “Fight!” Tommy has only one choice now.

Ben should know better and run when he sees the worm turn in Tommy’s eyes and resolve overtake surprise, but he keeps pressing, moving at Tommy like a clumsy, flat-footed cow. “Alright,” Tommy says as he quickly repositions himself to get more room to operate, and takes his fighting stance. He raises his fists to shoulder height and cocks his elbows level behind them, bouncing on his feet and bobbing his head back and forth as he transfers his upper body from one side to the other. Ben no longer has a stationary target, but the beer-muscles say it will be okay.

Ben plods on. Tommy says, “I don’t want to fight you!” one more time, and then launches a solid right cross with a thick-as-a-brick fist right at Ben’s eye. It seems like slow-motion as that meaty set of bone flesh comes sailing toward Ben, middle-finger knuckle at the point. It lands squarely on the bottom socket of Ben’s left eye, snapping his head back but not knocking him off his feet. He feels emboldened by weathering this initial blow and slogs at Tommy, his blood flowing warm with a little bit of beer.

Tommy snaps off another one and lands it on the same spot. Again, with the same results. Ben presses the attack like a wounded animal and actually thinks about trying to throw a punch, when Tommy says “Alright” again and pops off one more right cross – this time to finish, with a little heat – and puts it on the exact same spot, as though guided by a laser.

He immediately yells, “Ow! Fuck!” and grabs his right hand, pulling it to his body in pain. Ben thinks he has him now; but then his eye closes like an inverted vertical blind. Half his world goes dark, and the beer muscles melt away. Ben hears an adult say, “Alright, that’s enough!” All the other kids are yelling, “Take it outside!”

Tommy walks away snapping his right hand at his side and cussing. Ben turns his head with limited vision and finds his father in the bar, talking to his teacher, Mr. Doll. Ben tugs on his dad’s coat sleeve as the grown men look down at him.

“What the hell happened to you?” his father asks, looking a little shocked.

“I’m gonna go home now,” Ben says, and slowly walks away.

Ben’s father comes home a short time later and looks at Ben’s eye. “You okay?” he asks. Ben mumbles “Yeah,” kind of wimpily, just glad to be in the security of their house. Ben’s father looks at him sternly and says, “I asked around and everyone said you started the fight. Why would you do that? Tommy’s older than you?” Ben looks up at him through his good eye and mutters, “I thought I could win.” Ben’s father fetches some ice cubes in a wetted washcloth and says, “Just hold this on your eye. You’ll be alright.”

Ben sits in his father’s chair in the weathered-wood family room. His father turns the TV on for Ben and finds a show he likes (there are no remote controls back then, and only three channels because there are only three networks: ABC, NBC and CBS).

“You gonna be okay?” Ben’s father asks.

Ben nods and says, “Yeah, I’ll be fine,” already mesmerized by the black and white imagery from the General Electric console television set, it’s big wooden cabinet the size of their fireplace.

“I’ve got to get back to the ballroom,” Ben’s father says. “They’re our farmers and I want to talk to the families,” referring to the fact that the bride and groom families sell their milk to Ben’s family business, which turns it into cheese at the F.R. Rogue & Co. cheese factory (makers of Caroline Gold cheddar and Colby) since 1912. “I’ll be back to check on you in a bit. You sure you’re gonna be okay?” he asks.

“Yeah, I’m fine,” Ben says, transfixed by the magic of the vacuum tubes.

“Alright,” Ben’s father says, and he’s gone.

A few days later Ben is buying some fishing tackle at the Caroline Hardware, which is owned by a couple families in town, one of which is Ben’s buddy Scott Grosskopf’s. Mrs. Grosskopf is at the till and says, “Well look at you! That’s a nice shiner you have there. What happened?”

“I got into a fight at the wedding reception,” Ben says, somewhat sheepishly but with a little bit of pride.

“My my, that’s a nice one. What happened to the other guy?” she asks.

“I hurt his hand,” Ben says, and gives a little smile.

“Well, alright then,” she chuckles, and gives Ben a little pat, having raised enough boys to know that a little black eye is no big deal, just part of the rite of passage to becoming a man. Ben chuckles back and turns to leave, hoping Tommy’s hand feels better, and takes a few small steps out of adolescence. It occurs to Ben at that moment that, just maybe, everything really is alright.